항산화활성 최적 조건으로 추출한 산겨릅 열수 추출물의 LPS로 유도된 RAW 264.7 세포에 대한 항염증 효과

This is an Open-Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

In this study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of hot-water-extracts of Acer tegmentosum extracted under optimal conditions to maximize antioxidative activities with respect to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Acer tegmentosum extract was produced based on the response surface methodology (RSM). The result from a previous study (Kim et al. 2021) was used for the current investigation (extraction temperature: 89.34°C, extraction time: 7.36 h and solvent to solid ratio: 184.09). The optimized Acer tegmentosum extract remarkably inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-inducible nitric oxide (NO) secretion to culture media on RAW 264.7 macrophages. The pre-treatment of Acer tegmentosum extract also significantly prevented the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) from LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Therefore, the pre-treatment of the optimized extract based on RSM for maximizing antioxidative activities of Acer tegmentosum effectively attenuated LPS-inducible inflammatory responses in the murine macrophage cell lines.

Keywords:

Acer tegmentosum Maxim, anti-inflammatory effect, lipopolysaccharide, response surface methodologyI. 서론

염증반응은 신체에 물리, 화학적 외부자극, 세균감염 등의 다양한 기질 변화를 유발하는 손상이 발생하였을 때 이에 대응하기 위한 생리학적 방어작용이다(Kim et al. 2016). 염증반응시 면역세포는 다양한 염증 발현 단백질을 분비하여 손상 조직의 추가적인 감염를 막고 조직을 재생하여 정상화하려 한다(Nam & Park 2019). 염증반응은 급성과 만성반응으로 나눌 수 있는데, 자극원에 의해 특정조직에 손상이 있을 때, 호중구나, 호염구, 호산구, 단핵세포 등의 세포와 IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 등의 염증성 cytokine이 발현하여, 농양이 생성되고 통증이 완화되는 등 조직이 회복되는 과정으로 진행한다. 또한, inducible nitric oxide synthase(iNOS), cyclo-oxygenase-2(COX-2) 같은 효소나, nitric oxide(NO), prostagladin E2(PGE2) 등의 면역관련 물질을 생성한다(Jeong et al. 2014). 그러나 이러한 염증반응이 원인의 제거되지 않아 만성화되면 림프구나 체액성 면역 유도 cytokine과 세포성 면역유도 cytokine으로 주요 반응 물질이 지속적으로 발현될 수 있다(Carol & Timothy 1997).

대식세포는 비정상인 세포, 조직, 이물질, 세균 등 체내 존재하는 이상물질을 흡수하고 소화시켜 제거하는 식세포 작용하는 백혈구의 일종이다. 골수나 혈액에서 단핵구로, 간에서는 Kupffer cell로, 신장에서는 사구체 간세포, 신경계에서는 microglia 등 세포의 위치에 따라 적합한 형태로 몸 전체에 분포한다(Ovchinnikov 2008). 대식세포인 macrophage는 크게 M1과 M2로 분류되는데(Hesketh et al. 2017), M1은 interferon gamma(IFN-γ), LPS 등에 자극되어 iNOS 같은 물질과 TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 등의 염증성 cytokine이 발현하는 반면 M2는 IL-4, IL-13 등에 의해 자극되어 resistin-like-α(Fizz1), arginase1(Arg1), IL-10 등을 발현한다. Macrophage는 염증성 질환의 초기부터 휴지기까지 과정에서 분화 형태를 달리하여 항염증성 매개 물질을 분비하여 조직재생에 기여한다(Charles 2012).

추출은 식물 등의 혼합물질에서 특정 성분을 용매에 용해하여 분리하는 원리로서 여과와 원심분리와 함께 기능성 소재의 분리정제를 위해 쓰인다. 추출법은 용매에 혼합물질을 넣어 용매와의 친화력을 이용하여 분리하는 침출법을 기본으로 혼합물질에서 특정 물질을 효과적으로 분리하기 위하여 온도와 압력을 조정하는 가열추출법이나 속슬렛(Soxhlet) 추출법 등이 개발되었으며, 최근 물질의 상태를 바꾸거나 에너지 전달방식을 달리하여 분리하는 방법인 마이크로웨이브(microwave) 추출방법, 초음파추출(ultrasound assisted extraction), 초임계추출(superfluid) 법 등이 개발되어 추출에 쓰이고 있다(Azmir et al. 2013). 이러한 추출방법은 분리하고자 하는 물질의 효율적 분리를 위하여 개발되었으나 고도의 설비와 사용에 필요한 비용적 문제로 인해 선택적으로 사용되고 있다. 산업화 수준에서 추출방법으로는 비용이 적게 소모되고 추출조건 조절이 쉬운 장점이 있어 가열추출법이 범용적으로 사용된다. 가열추출을 위하여 선택해야 하는 요소들은 추출용매, 온도, 시간, 용매와 용질의 비율 등이다. 추출용매의 경우 혼합물질 내 분리하고자 하는 물질과 추출용매간의 극성차이가 적은 상태일 경우 용매에 균일하게 용해될 수 있으므로 추출효율이 달라진다. 또한 추출효율은 용매의 끓는점, 유효 물질의 온도에 따른 안정성에 따라 결정되며, 추출 시간의 경우도 추출 시간에 따라 유효물질의 분리가 부족하거나 활성이 저해될 수 있다. 또한 용매에 비해 용질이 과도할 경우는 분리된 물질이 용매에 완전히 이동할 수 없고, 용매가 과도한 경우는 용매와 용매를 가열하는 비용 뿐 아니라 추후 용매의 제거 시에도 경제적으로 비효율적인 추출이 될 수 있어 추출법을 선정한 뒤 적절한 추출조건의 설정이 필요하다(Azwanida 2015).

산겨릅 나무의 학명은 Acer tegmentosum Maxim 으로 단풍나무과 낙엽 소교목으로 분류되며 이명으로는 산저릅나무, 참겨릅나무, 산청목, 벌나무 등이 사용된다. 동북아시아 지역, 특히 국내 지리산부터 만주지역, 만주와 아무르, 우수리강 근처까지 고산지역에서 분포한다(Kwon et al. 2008). 산겨릅의 약리작용으로 작용하는 물질 후보로는 salidroside나, quercetin, catechin, coumarin(Park et al. 2006) 등의 페놀성 화합물도 활성을 보였으며 phenolic glycoside나 isoprenoid(Hur et al. 2007) 등의 물질도 검색되었다. 기능성과 관련하여 과거부터 간질환 관련 질환에 사용되었으며, 항산화나 항염증, 간보호 활성 등에 효과를 보였으며, 당뇨나, 항암효과와 관련한 기능성이 확인되었다(Lee et al. 2017a). 산겨릅 나무의 간기능 개선효과를 확인하는 연구를 시작으로 (Kwon et al. 2008) 다양한 기능성 연구가 보고되었으며, 산겨릅 나무의 추출물별 기능성물질의 분리에 대한 연구들도 다수 발표되었다(Table 1). 그러나 산겨릅 나무의 특정 성분의 분리 및 정제를 통한 기능성 성분의 효과를 검증하거나 추출물의 유효성분을 효율적으로 추출하는 연구는 용매를 바꾸거나 분획하는 수준의 설정만 진행되었으며(Kwon et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2017b; Lee et al. 2018) 추출방법에 따른 기능성 차이를 확인한 연구는 부족하다.

본 연구는 항산화활성 최적 조건으로 추출한 산겨릅 열수 추출물을 RAW 264.7 macrophage에서 처리하고 LPS로 염증반응을 유발하였을 때 염증유발을 억제하는지 평가하고 그 근거를 확인하기 위해 수행하였다.

II. 연구방법

1. 재료 및 시약

본 실험에 사용한 산겨릅(Acer tegmentosum)은 충북 제천에서 채취한 것을 구매하여 사용하였다. RAW 264.7 macrophage는 한국세포주은행(Korea cell library bank, Seoul, Korea)에서 분양을 받아 사용하였다. Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium(DMEM), fetal bovine serum(FBS), penicillin-streptomycin solution은 Welgene(Daegu, Korea) 제품을 구매하여 사용하였다. Lipopolysaccharide(LPS), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide(MTT), dimethyl sulfoxide(DMSO)는 Sigma-Aldrich에서 구매하였다(Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Moues ELISA Kit (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α)는 BD biosciences (Becton, Dickinson and company, Franklin lakes, NJ, USA)에서 구매하였다.

2. 추출물 제조

산겨릅 열수 추출물은 항산화활성 추출조건 최적화 선행 연구(Kim et al. 2021)에 따라 추출방법을 설정하여 사용하였다. 동일 농도의 산겨릅 열수 추출물의 항산화활성이 최고값에 이르는 조건을 설정하기 위하여 추출온도(X1: 70–90°C), 추출시간(X2: 2–6 h), 용매 대 용질 비율(X3: 50–150)을 조정하였으며, total phenolic contents와 DPPH radical scavenging activity 를 이용하여 최적 조건을 확인하였다. 모든 추출물은 세절한 산겨릅을 추출조건에 맞춰 추출하여 감압여과와 evaporator R-3000(Buchi Labortechnik, Frawil, Switzerland)를 이용하여 농축한 뒤 freeze drier는 FD8508(Ilshin Lab., Suwon, Korea)를 이용하여 동결건조한 뒤 사용하였다. 최적값은 response surface methodology(RSM) 중 Central composition design(CCD) 방법으로 예측하였다. 모델링한 RSM으로부터 total phenolic contents는 276.70 ± 10.11 mg GAE/g, DPPH radical scavenging activity 는 33.45 ± 2.20% 가 최대값으로 도출되었다. 최적 추출 조건은 추출온도: 89.34°C, 추출시간: 7.36 h, 용매 대 용질 비율: 184.09으로 최적조건이 확인되었으며 이를 기준으로 본 연구의 추출물을 제조하였다. 추출물은 위와 동일하게 농축과 동결건조를 통해 건조한 뒤 농도에 맞춰 실험에 사용하였다(Kim et al. 2021).

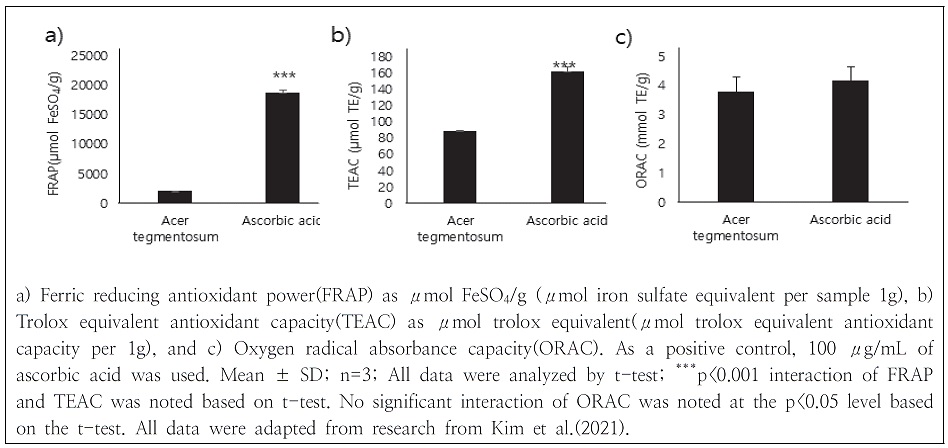

산겨릅 열수 추출물의 항산화활성 최적 조건을 기준으로 추출하였을 때, total phenolic 함량과 DPPH로 설정하며 추출온도: 89.34°C, 추출시간: 7.36 h, 용매 대 용질 비율: 184.09일때 최적 조건으로 확인되었고, 위 조건에서 항산화 활성이 있음을 Fig. 1에서 total flavonoid 함량, trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity(TEAC), ferric reducing antioxidant power(FRAP), oxygen radical absorbance capacity(ORAC)을 이용하여 측정하였을 때 기준으로 설정한 추출조건에 비해 각 263.31 ± 3.54 mg QE/g, 2,094.39 ± 43.43 μmol FeSO4/g, 89.31 ± 0.32 μmol TE/g, 3.80 ± 0.50 μmol TE/g 로 측정되었다(Km et al. 2021).

3. 세포배양

RAW 264.7 macrophage를 FBS가 10%, penicillin-streptomycin 1%가 되도록 Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium(DMEM)에 첨가하여 배양액으로 사용하였다. 세포배양조건은 37°C, 5% CO2를 유지하도록 하였다. 실험과정의 모든 세포는 80% 이상 채워지기 전 계대 배양하여 사용하였다.

4. 세포독성 측정

산겨릅 열수 추출물을 처리한 RAW 264.7 macrophage에 LPS를 가했을 때 산겨릅 열수 추출물의 염증예방 효과를 확인하기 위하여 MTT assay로 세포생존율을 측정하였다. 측정하고자 하는 산겨릅 열수 추출물은 0 - 40 μg/mL 농도범위를 설정하여 측정하였고 RAW 264.7 macrophage 5×105 cells/mL 농도의 96 well plate에 분주한 뒤 18시간 동안 배양하였다. 농도별로 희석한 산겨릅 열수 추출물을 처리한 뒤 1mM LPS를 처리하여 24시간 동안 반응시켜 배양한 뒤 MTT 용액을 첨가하고 4시간 동안 반응시킨 뒤 DMSO로 바꾸어 30분간 반응시켜 microplate reader(Spectra max M2, Molecular Devices, CA, USA)로 540 nm에서 측정하였다. 세포생존율의 계산은 다음과 같이 하였다.

5. Nitric Oxide(NO) 생성량 측정

Nitric oxide의 농도는 배양액 내의 nitrite 농도를 Griess’ reagent를 이용하여 측정하였다(Yee et al. 2000). Griess’ reagent는 2.5% phosphoric acid를 용매로 1% sulfanilamide 와 0.1% naphthalene diamine을 혼합하여 제조하였다. 세포를 phenol red가 없는 5% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin을 첨가한 DMEM 5×105 cells/mL 로 만들어 96 well plate에 분주한 뒤 18시간 배양하여 안정화한 뒤, 산겨릅 열수 추출물과 LPS를 처리하여 24시간 반응시켰다. 배양했던 상등액을 100 μL, 와 Griess’ reagent 100 μL룰 반응시켜 10분간 반응시켜 540 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다.

6. Cytokine 측정

산겨릅 열수 추출물의 염증 억제를 확인하기 위하여 RAW 264.7 macrophage에 산겨릅 열수 추출물과 LPS를 처리하여 생성된 IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α 분비량을 제조사에서 제시한 방법대로 측정하였다. RAW 264.7 macrophage 5×105 cells/mL 농도의 96 well plate에 분주한 뒤 18시간 동안 배양하고, 농도별로 희석한 산겨릅 열수 추출물을 처리한 뒤 1 mM LPS를 처리하고 다시 24시간 배양한 뒤 그 배지를 수확하여 샘플로 사용하였다. pH 9.5 인 0.1 M sodium carbonate, 1L 용액을 제조하고 각 항체를 분주하고 4℃로 1일간 암실에서 coating 되게 하였다. 이를 washing buffer로(0.05% tween-20이 포함된 PBS)로 3회 세척하고 assay diluent(10% FBS이 포함된 PBS)로 plate를 blocking 하였다. 샘플을 넣은 뒤 실온에서 반응시키고 다시 washing buffer로 5회 세척한 뒤 detection antibody와 Sav-HRP reagent를 혼합한 working detector를 well에 넣어주고 기질용액을 추가하여 30분간 암실에 방치하였다. 이후 1M H3PO4을 stop solution으로 넣어주고 450 nm에서 측정하였다.

7. 통계처리

실험결과의 통계처리는 Minitab 16.1.0(Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA)를 이용하였다. 모든 결과는 3회 반복실험하여, 평균 ± 표준편차로 나타내었다. p<0.05 수준에서 One-way ANOVA를 사용한 뒤 Fisher로 사후검정하여 결과간 유의성을 확인하였다. 추출물의 항산화활성 비교는 paired t-test를 이용하여 차이를 확인하였다.

III. 결과 및 고찰

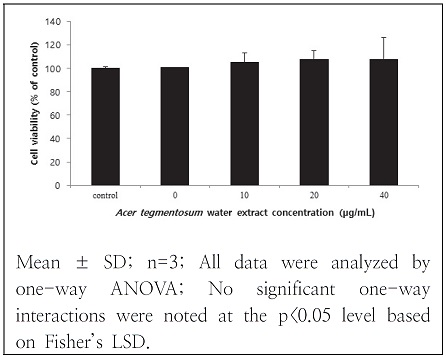

1. 세포독성 측정

RAW 264.7 macrophage에서 산겨릅 열수 추출물이 LPS에 의한 염증발현을 확인하기 위하여 MTT assay를 이용하여 세포생존율을 측정한 결과는 Fig. 2와 같다. 열수 추출물은 10 μg/mL, 20 μg/mL, 40 μg/mL 범위로 측정하였는데 대조군, LPS 처리군을 포함하여 모든 군은 유의적 차이를 보이지 않았다. Lee et al.(2018)의 연구에서는 water soluble tetrazolium(WST) 법을 사용하여 세포생존율을 측정한 결과에서 산겨릅 열수 추출물 6.25 μg/mL 에서 100 μg/mL 까지 세포독성이 없었다. 산겨릅 추출물은 용매에 따라 세포독성이 차이를 보이는데. Eo et al.(2020)의 연구에서 산겨릅 잎을 70% 에탄올을 용매로 추출한 물질의 세포별 세포생존율은 SW-480, PC-3, AsPC-1, A549, HepG2 cell에서 10% 이상 감소하였고, Lee et al.(2018) 연구에서도 산겨릅 90% 에탄올 추출물의 세포생존율은 100 μg/mL에서 90% 이하로 감소하였다.

2. Nitric Oxide (NO) 생성량 측정

NO는 L-arginine을 기반으로 하여 iNOS에 의해 생성되는 물질로(Weisz et al. 1996) 항염증과 염증조절에 관여하는 주요 인자이며 체내 유해 미생물 유입시 제거에 사용되기도 하며 염증관련 세포의 활성에도 영향을 준다(Posadas et al. 2000). NO는 또한 혈관 확장과 백혈구의 이동을 촉진하여 조직의 손상 등에 의한 복구를 위한 반응을 유도한다(Demiryurek et al. 1998). 하지만 과도한 NO의 발생은 과도한 염증반응으로 인해 세포 및 조직 손상이 일어날 수 있으며 만성 염증성 질환을 유발한다(Cho et al. 2015).

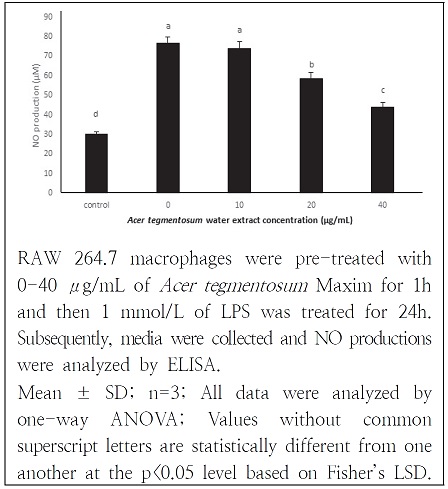

RAW 264.7 macrophage에서 LPS에 의해 유도되는 급성염증 반응을 산겨릅 추출물이 억제하는지를 확인하는 목적으로 NO의 생성량을 측정한 연구 결과는 Fig. 3와 같다. LPS에 의해 NO 생성량이 대조군에 비해 2.5배 증가하였고(30.02 ± 1.31, 76.69 ± 3.16) 산겨릅 열수 추출물의 농도증가에 따라 NO 생성량이 농도 의존적으로 감소하였다. Cell viability는 동일 농도에서 생존율의 차이를 보이지 않았으나 NO 생성량에 큰 변화값을 보여 급성 염증 반응이 정상적으로 진행되었고 산겨릅 열수 추출물이 저해물질로 작용함을 확인하였다.

3. Cytokine 측정

Macrophage의 경우 크게 생체 방어, 상처 치유, 면역조절작용으로 사용되는데, 그 중 regulatory T cell 로부터 생성된 macrophage는 반응에 영향을 주게 된다(Mosser & Edwards 2008). IL-10의 경우는 anti-inflammatory cytokine으로 알려져 있고, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 등이 대표적 pro-inflammatory cytokine으로 알려져 있으며 염증반응에서 cytokine의 균형이 중요하다(Stenvinkel et al. 2005). 염증성 cytokine 중 TNF-α는 염증, 세포증식, 분화, 사멸에 관여하는 cytokine으로 TNF-α와 receptor 등과 결합물이 nuclear factor kappa B(NF-κB)와 activator protein 1(AP-1) 활성화에 중요한 역할을 한다(Zelová & Hošek 2013). IL-1β는 염증반응과 세포증식, 분화, 세포사멸 등에 영향을 주며 COX-2와 iNOS 발현을 유도한다. TNF-α와 기능은 유사하나 골수세포를 증가하고 호중구를 자극하여 반응을 유도하며 세포사멸에 관여하지 않는다(Dinarello 2005). IL-6은 다양한 내분비 및 대사작용에 영향을 다발적으로 작용하는 물질로 초기 염증반응 뿐 아니라 류마티스 관절염 등의 만성염증성 질환을 유도하며 성장호르몬 분비 조절, 피로유발, 골다공증 등에도 영향을 미친다(Papanicolaou et al. 1998).

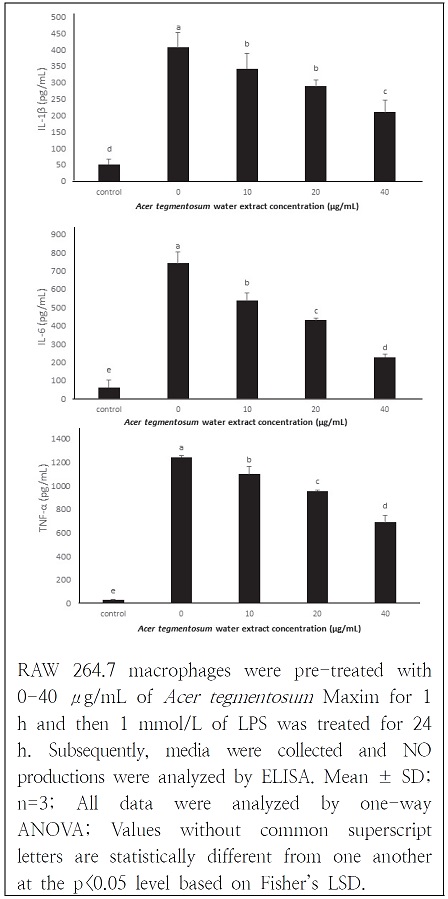

급성 염증반응에 대한 cytokine의 발현을 확인하기 위하여 IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α을 선정하여 산겨릅 열수 추출물과 LPS를 처리하여 cytokine의 발현양을 확인하였다. IL-1β은 LPS 처리 여부에 따라 51.13 ± 15.80 에서 407.54 ± 45.17 로 8배정도 증가하였으나 산겨릅 열수 추출물의 농도 의존적으로 감소하여 40 μg/mL 처리군에서 210.33 ± 36.45 로 절반 수준까지 감소하였다. IL-6도 LPS 처리여부에 따라 62.60 ± 40.33 에서 741.13 ± 61.79로 10배 이상 증가하나, 산겨릅 열수 추출물 처리에 따라 농도 의존적으로 감소하였다. TNF-α 또한 25.49 ± 6.44 에서 1,243.08 ± 16.13 로 50배 가까이 발현된 뒤 농도 의존적으로 감소하였다. 산겨릅의 주요 기능성 물질인 salidroside는 LPS에 유도된 RAW 264.7 macrophage에서 PGE2, TNF-α, IL-6 발현을 농도 의존적으로 감소시켰다(Won et al. 2008). 산겨릅 가지의 열수 추출물과 90% 에탄올 추출물의 TNF-α을 비교한 연구에서는 열수추출물이 에탄올에 비해 TNF-α를 적게 감소시키며, 100 μg/mL 에서는 TNF-α를 유의적으로 증가시키지는 않으나 소폭 상승시켰다. 또한 Yu et al.(2010) 연구에서도 70% 산겨릅 에탄올 추출물의 경우도 TNF-α가 감소함을 보였다. 산겨릅 열수 추출물의 유효물질로는 D-(+)-3-phenyllactic acid, 1,6-digalloylglucose, dihydro sinapyl alcohol, fraxetin, epicatechin 등으로 확인되었는데, 그 중 1,6-digalloyl glucose은(Tunalier et al. 2007) 털부처꽃의 유효성분으로 실험동물 수준에서 항염증활성을 확인하였으며, fraxetin은 동물수준에서 항산화, 항염증 활성을 보고하였다(Wang 2020).

The anti-inflammatory effect of Acer tegmentosum Maxim extract on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages.

NF-κB는 염증반응, 면역, 세포의 성장과 증식, 세포사멸 등에 아주 중요한 역할을 미치는 전사조절 집합체이다. 내독소 노출시 일반적으로 NF-κB의 활성화는 세포질의 inhibitor of NF-κB proteins(IκBs)의 인산화로 인한 프로테아좀 분해 및 인산기 전달에 의하여 진행되는 특징이 있다. 일반적인 경우 IκBs의 역할은 세포질에서 NF-κB와 결합하여 NF-κB의 활성화를 억제하나 염증 반응 노출시 인산화 되어 분해되어 NF-κB의 세포질에서 핵으로의 이동을 가능하게 한다(Oeckinghaus & Ghosh 2009). NF-κB의 핵으로의 이동 및 활성화는 염증 및 면역 관련 전사 인자 (예. IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α)의 활성화를 동반한다. 내독소 등의 노출로 세포내 염증반응의 증가시 세포내 염증 및 면역관련 mRNA의 전사 증가와 인산화를 통한 post-translational modification이 증가함을 알 수 있다(Ha et al. 2014). 본 실험에서 항산화 추출 최적화 조건에 의하여 열수 추출된 산겨릅을 RAW 264.7 macrophage에 처리한 경우 IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, NO의 cytokine 분비량이 유의적으로 감소함을 확인할 수 있었다.

LPS를 처리한 RAW 264.7 macrophage에서 산겨릅 에탄올 추출물의 항염증 효과를 확인한 연구에서(Yu et al. 2010) 산겨릅 추출물은 NF-kB 활성을 저해하는데, 그 중에서 radical에 의한 저해 유도가 아닌 extracellular signal-regulated kinases(ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase(JNK), p38 단백질의 인산화를 억제하여 NF-κB의 세포핵으로의 이동을 유적으로 저해함을 확인하였다. 에탄올 추출물은 유효성분이 salidroside로 NF-κB와 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)를 저해하는 물질로 알려져 있다(Xu et al. 2019). 그러나 salidroside는 열수 추출물에서는 거의 추출되지 않기 때문에(Table 1) 본 연구에서 사용된 산겨릅 열수 추출물의 항염증 반응은 fraxetin, epicatechin에 의한 것으로 추론할 수 있다. Fraxetin은 IL-1β로 연골세포의 염증반응에서 NF-κB p65 활성화 및 TNF-α, IL-6의 발현을 감소시켰으며, CCl4로 유도된 간세포에서 fraxetin에 의해 NF-κB, p-IκBα, p-p38 MAPK, p-JNK, p-ERK 발현 감소를 보여 인산화 경로를 통한 NF-κB-MAPK축 억제를 확인하였다(Wu et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2019).

본 연구결과와 이전 연구 결과(Yu et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2019)를 비교하여 볼 때 산겨릅은 내독소 처리에 의한 염증반응 억제를 확인할 수 있었다. 추후 연구에서 산겨릅의 항염증 효과가 전사적으로 조절이 되는지 혹은 post-translational modification에 의하여 진행되는지 그 구체적인 작용 원리에 대하여 심도있게 살펴볼 필요가 있겠다.

IV. 요약 및 결론

본 연구는 항산화 활성 최적화 추출조건으로 제조한 산겨릅 열수 추출물을 RAW 264.7 macrophage에서 LPS를 처리하여 급성염증을 유도하는 과정에서 추출물의 염증발현 저해를 확인하였다. 세포생존율과 NO 생성량 측정을 통해 세포의 NO가 LPS에 의해 발생함을 확인하였으며, 산겨릅 추출물을 미리 처리하였을 때, 농도 의존적으로 감소하였다. NO 발생을 확인하기 위하여 급성 염증발현의 인자로 사용되는 pro-inflammatory cytokine 3종(IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α)의 발현량을 확인하였을 때 세 cytokine 모두 LPS에 의해 급격한 증가를 보였으며, 산겨릅 추출물의 전처리에 의해 발현량이 유의적으로 감소하였다. 이를 통해 산겨릅 열수 추출물이 급성 염증 발현을 저해할 수 있음을 확인하였다.

Acknowledgments

These authors contributed equally to this work.

본 연구는 농림축산식품부 농식품기술융합창의인재양성사업(과제번호 714001-07)에 의해 수행되었으며 이에 감사드립니다.

References

-

Azmir J, Zaidul IS. M, Rahman MM, Sharif KM, Mohamed A, Sahena F, Omar A KM(2013) Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: a review. J Food Eng 117(4), 426-436.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.01.014]

- Azwanida NN(2015) A review on the extraction methods use in medicinal plants, principle, strength and limitation. Med Aromat Plants 4(196), 2167-0412.

-

Carol AF, Timothy MW(1997) Cytokines in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Biosci 2(1), 12-26.

[https://doi.org/10.2741/A171]

-

Charles DM(2012) M1 and M2 Macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crir Rev Immunol 32(6), 463-488.

[https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i6.10]

-

Cho YH, Kim HJ, Kim DI, Jang JY, Kwak JH, Shin YH, Cho YG, An BJ(2015) Effect of garlic (Allium sativum L.) stems on inflammatory cytokines, iNOS and COX-2 expressions in Raw 264.7 cells induced by lipopolysaccharide. Korean J Food Preserv 22(4), 613-621.

[https://doi.org/10.11002/kjfp.2015.22.4.613]

-

Demiryurek AT, Cakici I, Kanzik I(1998) Peroxynitrite: a putative cytotoxin. Pharmacol Toxicol 82(3), 113–117.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0773.1998.tb01408.x]

-

Dinarello CA(2005) Blocking IL-1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med 201(9), 1355-1359.

[https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20050640]

- Eo HJ, Park GH, Kim DS, Kang YG, Park YK(2020) Antioxidant and anticancer activities of leaves extracts from Acer tegmentosum Korean J Plant Res 33(6), 551-557.

-

Ha JH, Shil PK, Zhu P, Gu L, Li Q, Chung S(2014) Ocular inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress are attenuated by supplementation with grape polyphenols in human retinal pigmented epithelium cells and in C57BL/6 mice. Nutr 144(6), 799-806.

[https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.186957]

-

Hesketh M, Sahin KB, West ZE, Murray RZ(2017) Macrophage phenotypes regulate scar formation and chronic wound healing. Int J Mol Sci 18(7), 1545.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071545]

- Hong BK, Eom SH, Lee CO, Lee JW, Jeong JH, Kim JK, Kim MJ(2007) Biological activities and bioactive compounds in the extract of Acer tegmentosum Maxim. stem. Korean J Med Crop Sci 15(4), 296-303

-

Hou Y, Jin C, An R, Yin X, Piao Y, Yin X, Zhang C(2019) A new flavonoid from the stem bark of Acer tegmentosum. Biochem Syst Ecol 83, 1-3.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bse.2018.12.006]

- Hur JM, Jun M, Yang EJ, Choi SH, Jong CP, Kyung SS(2007) Isolation of isoprenoidal compounds from the stem of Acer tegmentosum Max. Korean J Parmacogn 38(1), 67-70

- Hur JM, Song KS, Choi SH, Yang EJ(2006) Isolation of phenolic glucosides from the stems of Acer tegmentosum Max. J Korean Soc Appl Bio 49(2), 149-152

-

Jeong DH, Kang BK, Kim KBWR, Kim MJ, Ahn DH(2014) Anti-inflammatory activity of Sargassum micracanthum water extract. Appl Bio 57(3), 227-234.

[https://doi.org/10.3839/jabc.2014.036]

-

Kim I, Ha JH, Jeong Y(2021) Optimization of extraction conditions for antioxidant activity of Acer tegmentosum using response surface methodology Appl Sci 11(3), 1134.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/app11031134]

-

Kim MJ, Bae NY, Kim KBWR, Park JH, Park SH, Choi JS, Ahn DH(2016) Anti-inflammatory effect of Grateloupia imbricata Holmes ethanol extract on LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 45(2), 181-187.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2016.45.2.181]

- Kwon DJ, Bae YS(2007) Phenolic compounds from Acer tegmentosum bark. J Korean Wood Sci Technol 35(6), 145-151

-

Kwon, DJ, Kim JK, Bae YS(2011) DPPH radical scavenging activity of phenolic compounds isolated from the stem wood of Acer tegmentosum. J Korean Wood Sci Technol 39(1), 104-112

[https://doi.org/10.5658/WOOD.2011.39.1.104]

-

Kwon HN, Park JR, Jeon JR(2008) Antioxidative and hepatoprotective effects of Acer tegmentosum M. extracts. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 37(11), 1389-1394.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2008.37.11.1389]

-

Lee CE, Jeong HH, Cho JA, Ly SY(2017a) In vitro and in vivo anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activities of Acer tegmentosum Maxim extracts. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 46(1), 1-9.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2017.46.1.001]

-

Lee J, Hwang IH, Jang TS, Na M(2017b) Isolation and quantification of phenolic compounds in Acer tegmentosum by high performance liquid chromatography. BKCS 38(3), 392-396.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/bkcs.11099]

-

Lee KJ, Song NY, Oh YC, Cho WK, Ma JY(2014) Isolation and bioactivity analysis of ethyl acetate extract from Acer tegmentosum using in vitro assay and on-line screening HPLC-ABTS+ system. J Anal Methods Chem.

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/150509]

-

Lee SR, Park YJ, Han YB, Lee JC, Lee S, Park HJ, Kim KH(2018) Isoamericanoic acid B from Acer tegmentosum as a potential phytoestrogen. Nutr 10(12), 1915.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10121915]

- Lee ST, Jeong YR, Ha MH, Kim SH, Byun MW, Jo SK(2000) Induction of nitric oxide and TNF-α by herbal plant extracts in mouse macrophages. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 29(2), 342-348

-

Mosser DM, Edwards JP(2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol 8(12), 958-969

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2448]

- Nam JH, Park SJ(2019) Inhibitory effects of ethanol extract from Vicia amoena on LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) indeed nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production in RAW 264.7 macrophage cell. AJMAHS 9(6), 443-450.

- Nugroho A, Park HJ(2015) HPLC and GC-MS Analysis of phenolic substances in Acer tegmentosum. Nat Prod Sci 21(2), 87-92

-

Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S(2009) The NF-κB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1(4), a000034.

[https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a000034]

-

Ovchinnikov DA(2008) Macrophages in the embryo and beyond: much more than just giant phagocytes. Genesis 46(9), 447-462.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/dvg.20417]

-

Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Manolagas SC, Chrousos GP(1998) The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Ann Inter Med 128(9), 127-137.

[https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00009]

-

Park KM, Yang MC, Lee KH, Kim KR, Choi SU, Lee KR(2006) Cytotoxic phenolic constituents of Acer tegmentosum maxim. Arch Pharmacal Res 29(12), 1086-1090.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02969296]

-

Piao Y, Zhang C, Ni J, Yin X, An R, Jin L(2020) Chemical constituents from the stem bark of Acer tegmentosum. Biochem Syst Ecol 89, 103982.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bse.2019.103982]

-

Posadas I, Terencio MC, Guillen I, Ferrandiz ML, Coloma J, Paya M, Alcaraz MJ(2000) Co-regulation between cyclo-oxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in the time-course of murine inflammation. N-S Arc Pharmacol 361(1), 98-106.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s002109900150]

-

Stenvinkel P, Ketteler M, Johnson RJ, Lindholm B, Pecoits-Filho R, Riella M, Girndt M(2005) IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α: central factors in the altered cytokine network of uremia—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Kidney Int 67(4), 1216-1233.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00200.x]

-

Wang Q, Zhuang D, Feng W, Ma B, Qin L, Jin L(2020) Fraxetin inhibits interleukin-1β-induced apoptosis, inflammation, and matrix degradation in chondrocytes and protects rat cartilage in vivo. Saudi Pharm J 28(12), 1499-1506.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2020.09.016]

-

Weisz A, Cicatiello L, Esumi H(1996) Regulation of the mouse inducible-type nitric oxide synthase gene promoter by interferongamma, bacterial lipopolysaccharide and NG-monomethyl-L-arginine. Biochem J 316(1), 209-215.

[https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3160209]

- Won SJ, Park HJ, Lee KT(2007) Inhibition of LPS induced iNOS, COX-2 and cytokines expression by salidroside through the NF-kappaB inactivation in RAW 264.7 cells. Korean J Pharmacogn 39(2), 110-117

-

Wu B, Wang R, Li S, Wang Y, Song F, Gu Y, Yuan Y(2019) Antifibrotic effects of Fraxetin on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis by targeting NF-κB/IκBα, MAPKs and Bcl-2/Bax pathways. Pharmacol Rep 71(3), 409-416.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharep.2019.01.008]

-

Xu F, Xu J, Xiong X, Deng Y(2019) Salidroside inhibits MAPK, NF-κB, and STAT3 pathways in psoriasis-associated oxidative stress via SIRT1 activation. Redox Report 24(1), 70-74.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13510002.2019.1658377]

- Yee S(2000) A study on characteristic of forest vegetation and site in Mt. Odae (II)-site of plant community in Tongdaesan. J Korean Soc For Sci 89(5), 552-563

-

Yu T, Lee J, Lee YG, Byeon SE, Kim MH, Sohn EH, Lee YJ, Lee SG, Cho JY(2010) In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory effects of ethanol extract from Acer tegmentosum. J Ethnopharmacol 128(1), 139-147.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.042]

-

Zelová H, Hošek J(2013) TNF-α signalling and inflammation: interactions between old acquaintances. Inflamm Res 62(7), 641-651.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-013-0633-0]